When “Resources Are Finite” Sounds Like Common Sense (But Isn’t)

A few days ago I found myself in a late-night conversation with a friend about wealth and inequality.

He said, with great conviction: “The problem is that resources are concentrated in a few hands. Resources are finite, so when someone has more, others inevitably have less.”

It sounded serious, realistic, even obvious.

But a small voice in me whispered: “Are you sure?”

I started asking myself:

If resources are truly finite, how would we measure them?

Could we actually count every unit of wealth, every opportunity, every piece of knowledge in the world?

What about the way new ideas, technologies, and even life itself constantly emerge and expand?

That moment was my personal encounter with something psychologists call the illusion of explanatory depth — a cognitive bias that makes us overconfident in how much we understand.

What Is the Illusion of Explanatory Depth?

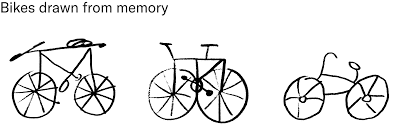

The term “illusion of explanatory depth” was first described by Rozenblit and Keil (2002) in a classic paper. It refers to our tendency to believe we understand something much better than we actually do — until we’re asked to explain it in detail. Only then do we discover the gaps in our explanatory knowledge.

This bias overlaps with the overconfidence effect and is related to the Dunning–Kruger effect: when familiarity feels like understanding, our confidence outpaces our actual knowledge.

Why This Matters in Everyday Rhetoric

The phrase “resources are finite” is powerful because it sits on two psychological pillars:

- Familiarity: We’re taught from childhood that there’s “not enough for everyone” and that “being realistic” means accepting limits.

- Authority of scarcity: Scarcity feels serious. It makes us look mature, responsible, grounded.

Combine those with the illusion of explanatory depth and you get a statement that feels undeniable but rarely gets examined. Most people who repeat it could not define what “resources” means in detail, nor explain how the limit is measured. Yet the phrase keeps its aura of truth.

This same dynamic shows up in other domains, too. In spiritual or self-help circles, for instance, a teacher may use lofty language and vague but authoritative claims to appear deeply knowledgeable. This can create a powerful but misleading sense of trust. If you’re curious about how to recognize this pattern, see our related article: “When Spiritual Wisdom Becomes Emotional Manipulation: How to Spot a Fake Guru!”.

From Rhetoric to Manipulation

This is also how rhetoric works.

Rhetoric is not necessarily manipulation; it’s simply the art of using language to persuade. But vague, emotionally loaded statements are fertile ground for manipulation because they exploit our cognitive shortcuts:

- A strong, simple phrase creates the appearance of knowledge.

- People hesitate to question it because it seems self-evident.

- It frames the conversation (“there is a fixed pie”) before any evidence is discussed.

If you want to control a narrative, you don’t have to prove a statement; you just have to make it sound like common sense.

Practising Critical Thinking and “Critical Rhetoric”

One antidote is what I call critical rhetoric: learning to pause and gently interrogate statements that sound obvious.

When someone says “resources are finite,” you might ask:

- “Which resources exactly? Money, land, knowledge, opportunities?”

- “How would we measure the total?”

- “Is this always true, or only in some contexts?”

Sometimes the point isn’t to win an argument but simply to open a window of reflection. Even just asking the first question is often enough to reveal how little detail is actually there.

Closing Thought

The illusion of explanatory depth isn’t a flaw of other people; it’s part of being human.

But when we become aware of it, especially in phrases that sound “realistic,” we give ourselves a chance to step out of automatic thinking. We can separate facts from frames, and choose which stories we accept about scarcity, abundance, and what’s possible.

Recommended Reading

If you’d like to dig deeper into how we misinterpret data, arguments and “common sense,” I recommend The Data Detective by Tim Harford. It’s an accessible guide to spotting misleading claims and sharpening your critical thinking.